I met Julia Schlosser at my Annenberg lecture in February of 2016. It was then that she told me about the art component of the Living with Animals conference, Seeing with Animals (the 2017 inaugural conference of which Julia chaired). Since then, Julia and I have worked together on Seeing with Animals and the exhibition she curated earlier this year, Remembering Animals: Rituals, Artifacts and Narratives. Through short visits and many long phone calls, I have gotten to know Julia and her work well. When I felt ready to recommit to posting regular on Muybridge’s Horse this summer, featuring Julia’s photography felt like the perfect way to start.

I reached out to Julia a little over a week ago to ask if she would be interested in having two of her older series, Contact and Tend, featured on MH. She responded the next day – her 18-year-old cat, Alex, had died just a few days before, and she had made some images at the pet cemetery and a few cyanotype photograms of his body and some “lasts” – last bowl of water, last meal, last pills, etc. I was struck by not just the images Julia sent, but the fact that she felt prepared to publicly share these images and her experience so shortly after Alex’s death. It reminded me of when my own cat, Candy, died almost two years ago at age 17 and how, in the week after her death, I spent a lot of time looking at my photos and videos of her and writing about her death. In the ten days since I asked her to, Julia has written an incredible statement to accompany the images she made during her experience after Alex’s death. It is a longer statement than I would normally include; because it is so lovely and so important, I want to feature it in its entirety here.

Alex and Sebastian were brothers, brown and white tabby kittens, who first lived next door to me with a neighbor overburdened by her life circumstances. At a certain point when they needed a new home, the two adolescents came to live with me. Early in our relationship, I was back in graduate school and making art again after a gap. I reconnected with my passion for art-making and criticism through the animals with whom I lived. This was an exciting time for me. Alex and Sebastian both had indomitable senses of adventure and great spirits of discovery, resilience, and energy. They were never afraid of my cameras and welcomed the time we spent together photographing.

I made thousands of photographs of Alex and Sebastian over several years as I was discovering the rich body of criticism and theory concerning representations of animals. Making and viewing their photographs increased my comprehension of the powerful messages animal representations can convey. Our collaborative activities propelled my understanding of what it means to live with animals. They helped me discover subsequently deeper and more nuanced aspects of our inter-species relationship. I strove to make visual what I understood from these cats.

While Alex and Sebastian were the leaders of the animal community at my house, both suffered from immune deficiency diseases. Treating their diseases required daily care, and this treatment found its way into my art-making practice. Sebastian died over a year ago. I expected his loss to rock the household, but we all sadly moved on without much ado. When Alex died, I thought it would be the same. I didn’t realize the intricate ways that the web of his beloved energy was holding our family in balance. We’ve all suffered tremendously for his loss.

A week before I decided to euthanize Alex, he moved off his place next to me on the sofa into a far corner of the room. This was his way of signaling that it was time to go. The vet took blood. The tests came back and, no surprise to me, his numbers had crashed. The morning before we went back to the vet for his ultimate visit, he ate an unexpected amount and walked slowly around the yard, then drank from his water bowl, like he was preparing for the journey onward.

When it became apparent that I was going to euthanize Alex, I was so exhausted and sad that I didn’t think I could create any new images to honor his passing. But slowly the idea of making a cyanotype photogram of his body emerged. After he died, I brought his body home and spent time arranging him on the sun paper. While the paper exposed, I watched him bask in the sun for the last time. It was very comforting.

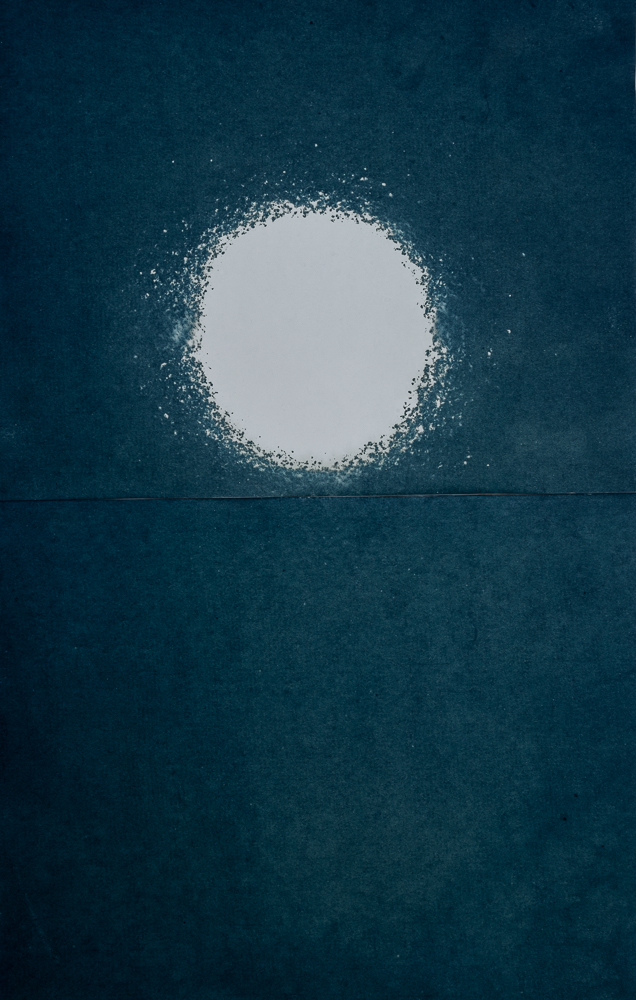

After I finished making the photogram, I brought Alex to the Los Angeles Pet Memorial Park, but it was too late in the day for him to be cremated. I left his body overnight and came back for the cremation the next morning with my camera. I photographed him for the final time as I witnessed his body being transformed into bits of bones and dust.

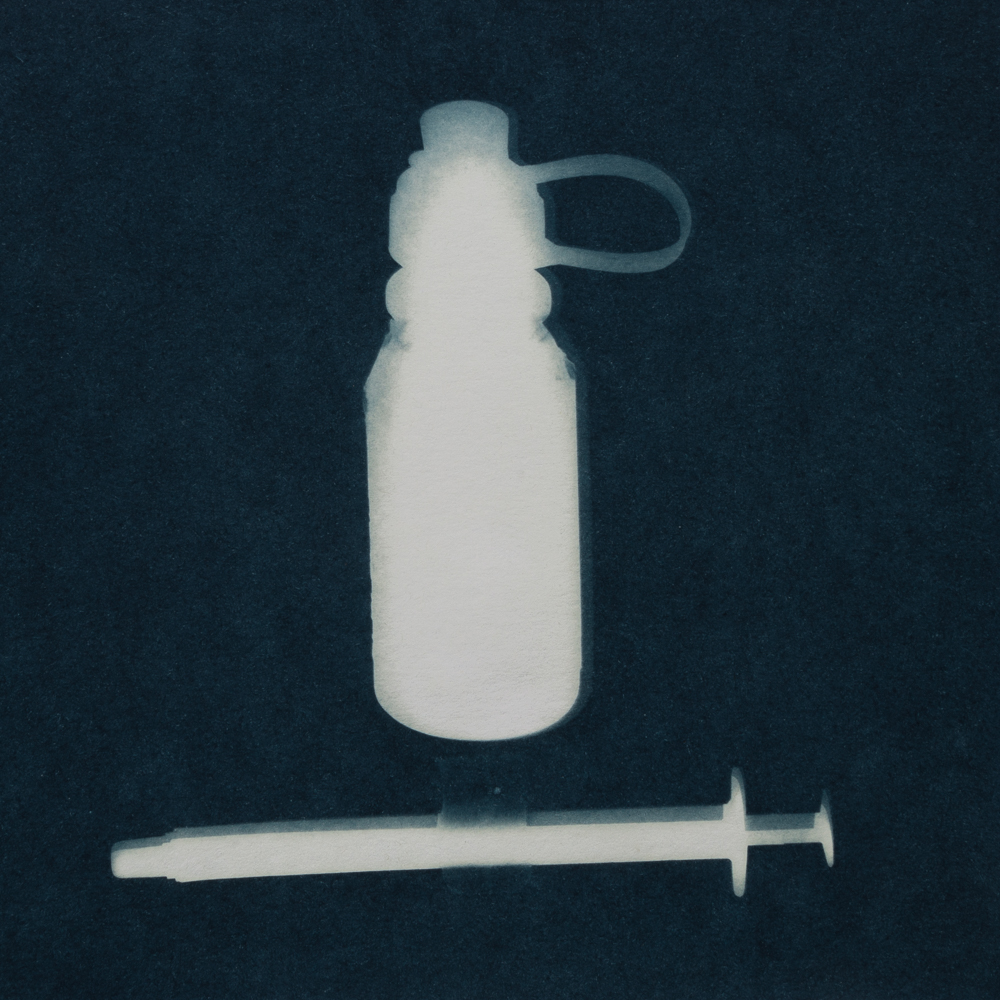

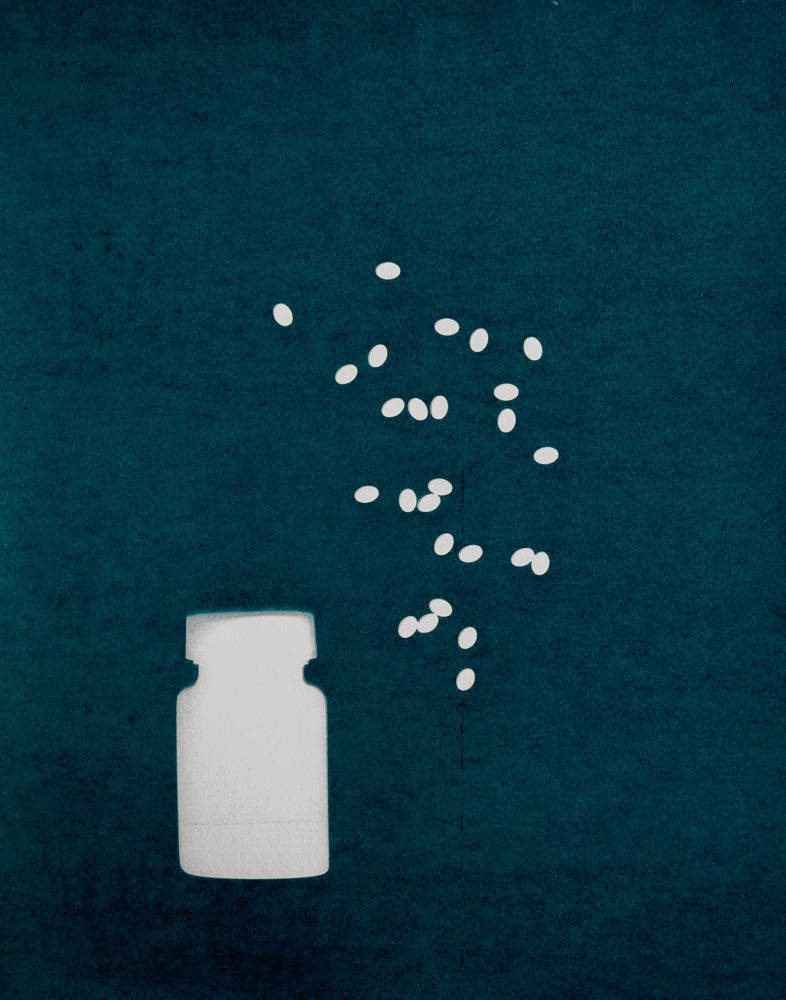

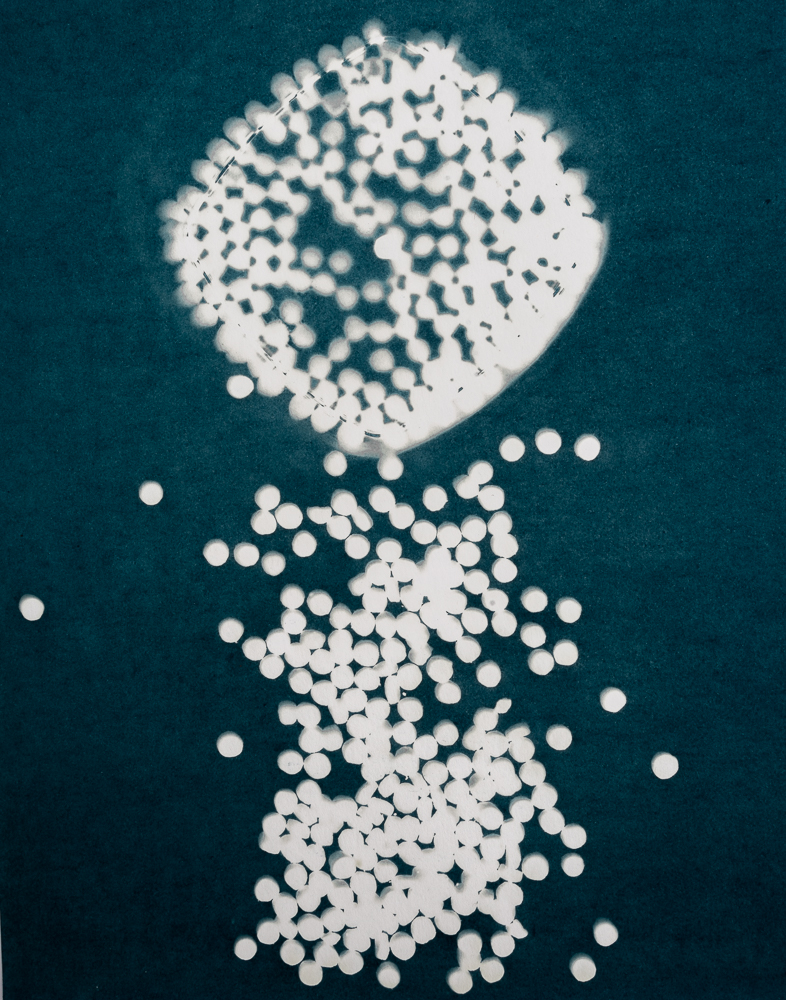

Carolee Schneemann’s film Kitch’s Last Meal was a revelation to me when I first saw it. It celebrates the vibrant agency of companion animals and the power of creating art about inter species connections. Unlike Schneemann, I knew in advance when Alex’s last meal was going to be. I saved the cans and jars and food and water bowls from his last days, along with medication bottles, syringes, and fur from his brush. From these, I created some additional photograms as a tribute to his final release of love. Alex died on the morning of Thursday, July 19, 2018.

Cat fur (last time I brushed Alex) from the series Alex Passing, 6×6″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

Azithromycin-oil 50 mg/ml SUSP, give .7 ml (35 mg) by mouth daily for 7 days (Alex’s medication for his chronic sinus infections came from a compounding pharmacy, last bottle dated 2/5/2018) from the series Alex Passing 6×6″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

Methylprednisolone 4 mg tablet, give ½ tablet by mouth twice a week, quantity 30 (5/30/2018, 26 tablets remain) from the series Alex Passing, 11×14″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

Hill’s Prescription Diet k/d Kidney Care with Chicken Dry Cat Food™ and plastic container, #2. (I kept Alex’s food in a plastic container by my bed so I could feed him several times every night, this is the food that was left over when he died) from the series Alex Passing, 11×14″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

Alex (Alex’s body) from the series Alex Passing, 28x 22″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

Alex (Alex’s cremains) from the series Alex Passing, 14×22″ cyanotype photogram, 2018

From “Alex Passing”

Visit artist's site: juliaschlosser.com

Posted August 2nd, 2018