I remember seeing the movie Babe as a six-year-old and my enchantment with animals transforming to something completely new. The same thing happened when reading Animal Farm some six years later. The concept that animals could be beings like humans, capable of complex thought and conversation, and not in a cartoon, Disney-movie way, changed the way I thought about and interacted with animals. I felt like not only could I see animals, creatures commonly thought to be on earth solely for man’s enjoyment, entertainment, and consumption–animals could see me.

Rob MacInnis’s photographs are about seeing animals, both how we as humans see animals and how these creatures are animals who see. These “common” animals–sheep, goats, cows, horses, dogs, and birds–are arranged before the lens as if on their marks, ready for their performance to start. They seem aware of our presence, our watching, and unfazed. But it feels like they’re up to something, like there’s much more going on behind those inhuman eyes than what’s visible on the surface.

Although it’s longer than what I normally include, I’m posting MacInnis’s statement in its entirety. For me, it informed the pictures in a way I haven’t seen many other statements do, and the questions it suggests are worth the read.

From the artist’s statement: “We do not identify dogs in terms of their physical characteristics… They’re identified in terms of our mental constructions, so they’re basically mental objects.” – Noam Chomsky, “Is the Man Who is Tall Happy?”

I remember a potent thought I first had as a kid at my family’s cottage on the Northumberland Strait, sitting on cheap reclining lawn chairs one October night. I inhaled the cool air from the shore as my mind was blown by my cousin’s descriptions of the impossible heavens above. During a little silence, I had a big thought: “What would it be like if the universe had never existed?” I tried hard, but couldn’t imagine. It was an odd thought, though a pleasingly impossible one which I tend to revisit with the same frequency as my attempts to learn the elusive art of whistling. “Could whistling create a portal to another universe?!” may describe how I approach my artworks/projects/distractions/displays-of-affection. Throwing rocks as far out to sea as I can, resulting in ever-pathetic, humorous and inevitable failures that re-verify the limits of my own present reality. The rocks always land somewhere between me and the waterfall at the end of the ocean, rubbing the real and the imaginary together.

Years later, as John Cage became the patron saint of my contrarian heart, I day-dreamed that these failures were not inevitable. Every limiting parameter signified a space beyond [its] edge. The trick I learned from my smarter older brother, that it’s impossible to look at a word without reading it, felt more like a challenge than a rule. I wondered if I could look an animal straight in the eye and make no assumptions about [its] thoughts.

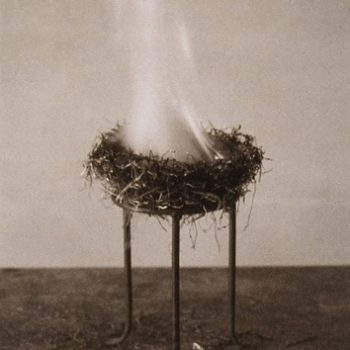

I blew large, uneasy shiny bubbles, anti-photographs of animals. And if you looked close in the right light you would see contained within, the apparition of perfected human bodies and photography’s ability to forever justify its exploitations. Something Lorrie Morre said, “I would never understand photography, the sneaky, murderous taxidermy of it.” To be honest, I am shy and people frightened me. Animals only pooped on your shoes.

I wondered if you projected enough white light onto black, would it disappear? Would the result be the negation of both, something new or just the impartial, toothless arbitrar? Could I ever see an animal? Or realize what seeing it means? I wanted to catch myself not seeing them. If I made them look like us, simply by virtue of my sharp aim, my repetitive and singular approach, my stylish bag of photo tricks, what would be the reflection? If I blew a bubble shiny enough, attractive enough, as impeccable as the polished mirror in a deep-space telescope: would it perfectly reflect us, richer than before? Can we really only see our own creations and nothing else?

It’s truly bizarre to tell people you have never seen these animals, but have only thought of them. That they can’t see this donkey, posed as a fashion model, because everything inside of a photograph is a hallucination. Trying to make animals disappear is about as hard as imagining the opposite of the universe but it’s well worth the effort.

From “The Dog & Pony Show”

Visit artist's site: robmacinnis.com

Posted September 7th, 2016